|

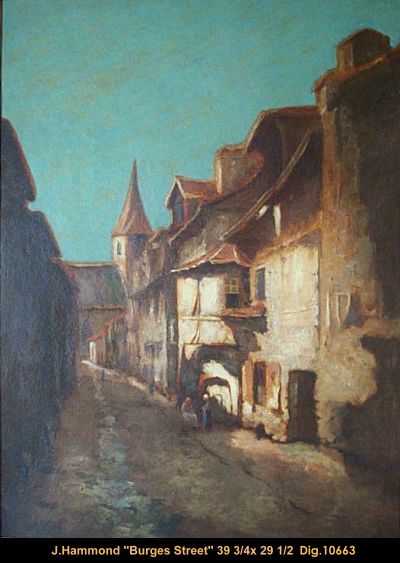

La vie de certains tient plus du roman que de la biographie. C’est

le cas de John Hammond, né à Montréal en 1843, qui a vécu près d’un

siècle tout en peignant une multitude de tableaux et en parcourant

la terre en tous sens. Sa manière de vivre et les nombreux endroits

qu’il a visités font qu’il est impossible de considérer son œuvre

sans évoquer ses pérégrinations.

Suivant la tradition, toujours vivace, la plupart de nos artistes

allaient en

Europe (c’est toujours l’Europe

ou encore New-York) pour parfaire leur instruction. Ce que firent

Lyman, Franchère, Borduas, Morrice, Suzor-Côté, pour n’en nommer que

quelques-uns. Tout ce monde-là est sédentaire comparé à

Hammond.

À l’âge de neuf ans,

Hammond travaillait déjà pour son père, marbrier, à qui il répugnait

d’engager des mains étrangères. À 11 ans, notre homme décide qu’il

serait artiste-peintre. Deux ans plus tard, il s’engage dans un

régiment surnommé « Les favors de ces dames » pour aller combattre

les Fenians, membres de la Fraternité Irlandaise républicaine aux

Etats-Unis, qui luttaient pour l’indépendance de l’Irlande et

s’attaquaient à l’Angleterre via le Canada…

Quelques mois plus tard, il part pour Londres, accompagné de son

frère cadet, à bord du Peruvian. Il y demeure un temps, puis

s’embarque sur le voilier Mermaid à destination de la Nouvelle-Zélande.

Le voyage dure quatre mois! Ce qui les attirait, lui et son frère,

c’était une « ruée vers l’or », le pays étant censé regorger de ce

métal précieux. Arrivés à

Christchurch, les deux frères marchèrent sur une distance de près de

200 kilomètres jusqu’au fictif Eldorado.

En 1869, après deux ans et demi de labeur sans profit, notre épris

d’aventures prit le bateau pour revenir à Montréal. Mais ce ne fut

pas pour longtemps, ayant à nouveau des fourmis dans les jambes. Il

travaillait chez Notman, le célèbre photographe de la Métropole, où

il transformait des photographies en petits tableaux en y ajoutant

de la couleur. Or, les Service d’études géologiques du

Canada cherchait des hommes pour faire de la recherche afin de

construire une voie ferrée entre l’Ontario et le Pacifique, et

s’était adressé à Notman. Ce dernier lui en fournit deux :

Hammond

fut choisi à titre d’assistant de Benjamin Baltzly. |

|

|

Hammond

redevient pèlerin. Il parcourt le Japon, toujours armé de sa

palette. Un jour, après avoir reçu une commande du

Canadien Pacifique,

il part pour Londres afin d’y exécuter une murale dans les bureaux

de cette entreprise. L’année suivante, il s’installe à St-John,

N.B., où il a été nommé directeur de la Owens Art Institute.

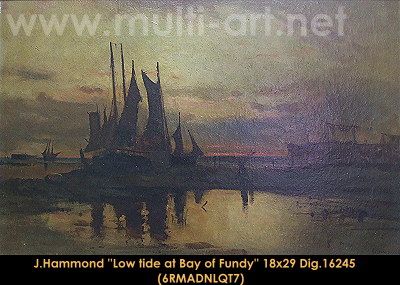

Naturellement, et sans doute à cause de l’influence de Whistler,

il

peint des scènes de port, de bateaux de pêche et de marines aux tons

embués. Le port de St-John est à lui ce que Venise était pour

Whistler.

Bien que peu connu des Québécois,

Hammond avait une solide réputation auprès des milieux anglophones.

Nommer quelques-uns de ses contemporains – Harry Rosemberg, Edward

John Russell, etc.-, c’est faire allusion a une génération presque

oubliée. Il reste que Hammond était devenu, en 1890, à l’âge de 47

ans, membre de l’académie royale des arts du Canada et qu’il dirigea

pendant longtemps la Owens Art Institute, laquelle devint une

faculté de l’Université Mount Allison, à Sackville, N.B., en 1907.

C’est dans cette ville que

Hammond

passe le reste de ses jours, et où il est mort en 1939 à l’âge de 96

ans.

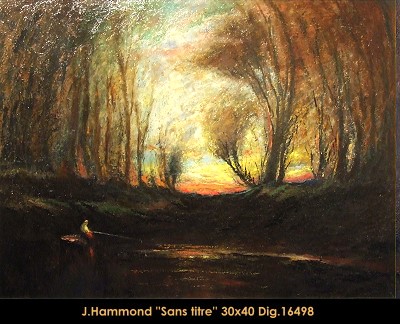

La production de

Hammond est abondante. On retient surtout ses paysages de

l’hémisphère boréal, qui vont des Rocheuses et de la côte Atlantique

aux campagnes d’Asie, en passant par la Hollande et ses moulins,

l’Italie – Venise, Veron, etc. -, la France champêtre et plusieurs

pays aux couleurs particulières.

Les paysages de

Hammond sont pleins de grands espaces et constituent de magnifiques

études des variations de la lumière du jour rendues avec finesse et

minutie. L’eau et tout ce qui s’y rattache y jour un rôle essentiel,

ce qui se traduit par d’exquis dégradés et par des teintes presque

évanescentes. On peut, sans exagérer, parler de classicisme et

d’amour de la nature. Hammond a été le chef incontesté d’une

génération d’artistes qui nous a fait, pour ainsi dire, découvrir le

Canada

et nous doter d’une riche tradition.

On ne louera jamais assez le mérite des

Hammond, Verner, O’Brien, Fowler, Edson et autres. Si la peinture a

existé ailleurs qu’au Québec et avant l’avènement de

l’impressionnisme, c’est grâce à eux.

Paul Gladu, (Magazin’Art, 10e Année, No 3, Printemps 1998)

He had a tough childhood, already working at age 9 in a factory

polishing marble. A jack-of-all-trades during his teens, he

enlisted in the army in 1866. After his demobilization, he left

for

London, England, then for New Zealand where he became a gold

digger for three years. When he came back to

Canada, he worked as a railroad worker in

Western Canada.

The paintings and drawings he executed at the time helped him to

produce murals commissioned by C.P.R. Then he came back to

Montreal the following year where he colorized the photographs

taken in black and white in order to make them real paintings.

Lives and Works of the Canadian Artist

John Hammond’s work has been neglected in the literature on

Canadian art history but in his own time he was well loved and

supported by the public, and respected and recognized by his own

fellow-artists. Throughout an active career that spanned nearly

seventy of his ninety-six years,

Hammond was deeply involved with

Canada’s

artistic activities and aims.

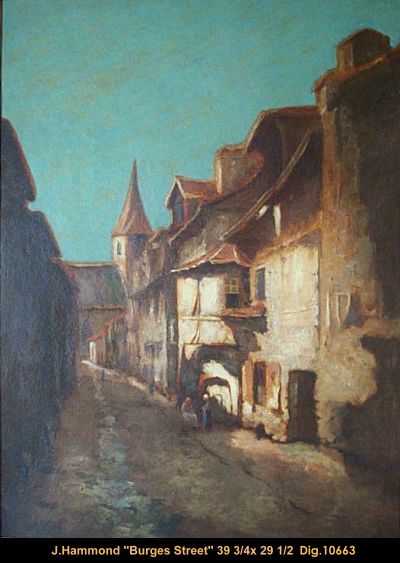

The problems which faced

Canada’s late-nineteenth century artists were not simple: there was

a desperate lack of art schools and financical support for the arts,

so that many painters went to Europe to study. When they returned

they were subjected to diverse pressures. On the one hand the

public, with its painfully conservative tastes, demande European

styles; on the other, the art critics exhorted, scolded and

persuaded Canada’s artists to formulate a “national style”. Only a

few critics realized that a national style involved centuries of

evolution. Representative of this era, John Hammond was brought up

in

Montreal

where life styles still clung tenaciously to the

Old World;

later he spent several seasons in

Europe

where he absorbed past and current artistic styles and conventions.

John Hammond was a painter of the landscape, seascape and the

mountains. He did not restrict himself to purely Canadian subjects;

many of his works portray scenes from

Europe,

the Eastern United Sates, China and Japan. But his name is most

readily associated with two Canadian gerographical areas: the New

Brunswick coast and the

Rocky Mountains. The activities which he undertook in these two locales are

reflective of important events in

Canada’s art history.

Hammond

settled in New Brunswick in the 1880’s where he

became the principal of the new

Owens

Art School in Saint John; in 1894 the School moved to Sackville,

N.B., where it received recognition as one of the most important art

educational centres in Eastern Canada. The coasts of the

Bay of Fundy,

from Sackville to

Saint John,

provided Hammond with innumerable subjects, and he became well known

as a marine artist. His sea paintings have erroneously been labelled

as entirely derivative of J.M.W Turner (1775-1851) and other

contemporary English and Dutch marine artists, but J. Russell Harper

in Painting in Canada (1966) was the first to recognize that

Hammond’s

aesthetic was far closer to that of James McNeill Whistler

(1834-1903), the expatriate American artist with whom he studied

briefly in Dordrecht. The entire canvas of a typical

Hammond

sea picture consists of a plane of low-toned, soft monochrome;

against this background Hammond introduces the minimal pictorial

elements with a few decisive brushstrokes of darker colour.

Hammond’s monochromes were not achieved by the use of one tone;

rather, he almost embroidered the canvas with daubs of pinks, pale

blues, greens, golds and yellows which, at close range, make the

picture alive with colour and, at a viewing distance, pull together

to form a poetic composition of colour and, surprisingly, strongly

realistic images which capture the strange hues, tecture and expanse

of the Bay of Fundy fogs.

Late in 1880’s

Hammond met his most important patron, Sir William Van Horne

(1843-1915), the President of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Van

Horne conceived of a promotional campaign in which he would send

some of Canada’s best artists to paint the scenery along the railway

routes. These paintings were then hund in hotels, stations and

offices, rather like the moderne travel poster. From 1891 to 1906

Hammond

painted intermittently for the C.P.R., his commissions taking im as

far as China and Japan when the steamship tours to the Orient were

initiated. It was an important era for Canada, and Hammond’s C.P.R

paintings represent a unique artistic and historic period in

Canadian art. “The Three Sisters” (Glenbow-Alberta Institute,

Calgary) is an example of his

Rocky

Mountain paintings. It typifies the artist’s efforts to overwhelm

the viewer with the grandeur and beauty of the mountains. It is a

successful, deliberate, large-format advertisement, but compared to

it, certain preliminary spontaneous. The paint is applied

vigorously, in large, elemental streaks of colour which seem more

responsive to the massive rawness of the mountains.

Hammond

was above all a sea and mountain painter, but he was alson known for

his pastoral landscapes. “Cold-stream Ranch” (Glenbow-Alberta

Institute), depicting the homestead of Lord and Lady Aberdeen in

British Columbia, demonstrates a

characteristic feature of all

Hammond’s

paintings: a tremendous sense of space and depth, of light and

atmosphere. Hammond has stepped back from the scene to take a

panorama wiew, thus achieving in his paintings an element that was

special to the Canadian landscape: vastness of land and sky.

Hammond’s involvement with the C.P.R. in the opening of the West,

and with the Owens Art School at a time when art education was

struggling for recognition, are evidence enough that he was an

important artistic, art-historical and historical personality, and

very much a representative figure of his era. He was a member of the

Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and participated regularly in the

Academy’s annual and international exhibitions.

The public’s taste in

Canada at the turn of the century has generally been acknowledged as

undiscerning. Thus, through unfortunate association,

Hammond’s

work, which originally found os much favor with the public, has more

recently been dismissed as uninspired.

Hammond

did not paint ot suit the public, but rather continued in his own

way with a dedication, discipline and sincerity which grew out of

his deeply religious life. Because of his poetic, gentle temperament

his paintings possessed, on a superficial level, the same qualities

which appealed so much to the sentimentalism of popular taste. A

closer study of Hammond’s work reveals him to be a much more

prominent figure of his artistic generation (particularly as a

Maritime and Rocky Mountain painter) than has hitherto been

acknowledged. |